How Dolf and Bev came into the Maxtone-Graham world

By Ysenda Maxtone-Graham

(The key player in all this is Joyce Maxtone-Graham, born Joyce Anstruther, and better known to the reading public as Jan Struther, who wrote the best-selling book Mrs. Miniver, based on her wartime newspaper columns. (She formed her pen name by changing J. Anstruther to Jan Struther.) Mrs. Miniver was adapted into a 1942 film of the same name, which was a hit on both sides of the Atlantic, and won six Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.)

First of all, Dolf:

In my biography of my grandmother Jan Struther, The Real Mrs. Miniver, I describe the moment when Jan (then known by her birth name of Joyce), still supposedly happily married to my grandfather Tony Maxtone-Graham, first met Dolf Placzek.

It was love at first sight, between a 38-year-old married British writer and a handsome Viennese man a foot taller and thirteen years younger. It’s not often that “love at first sight” really does mean a true meeting of kindred spirits and souls: a love that lasts and is real. But it did. They fell in love over a cup of tea and a rock cake at Lyon’s Corner House in The Strand, London, at teatime on Tuesday, November 21, 1939.

Dolf had arrived in London the previous March, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Vienna. His life and prospects had been turned upside-down three days after the Anschluss, when he was summoned to the office of the Director of Vienna University, where he had been studying Art History, and was told “There will be a way for you, but not here. I wish you well.”

In the rabidly anti-Semitic climate in Austria, it soon became clear that there was no “way” for Dolf anywhere in the country. The inky “J” on his passport indicated that he was on the list of persecuted outcasts. But in one way, he was lucky: a rich old lady friend of the family in New York, Anne de Tapla, sent an affidavit to Vienna which secured Dolf a place on the waiting list for the United States. With this in hand, he obtained a “transit visa” for England. It read “Good for one journey only.”

Two of Dolf’s cousins, Ernst and Franz Philipp, also managed to get out. The three young men rented seedy lodgings at 100 Denbigh Street in Pimlico. Uprooted and dejected, they wrote sad poems in German and tramped the London streets for hours on end. Dolf managed to get a part-time job working as an interpreting clerk at Bloomsbury House, the place where refugees queued up for clothing, food, a weekly handout of money, and help with paperwork.

Joyce Maxtone-Graham was friends with Sheridan Russell, who ran the Financial Guarantees desk at Bloomsbury House. Joyce – I’ll call her Jan from now on, to avoid confusion – had written the “Mrs. Miniver” columns for The Times, which had been published in book form by Chatto & Windus in October 1939. Inspired by the housewifely saintliness of her fictional creation, Jan started working part-time at Bloomsbury House, helping to sort and distribute clothes donated by Londoners to the refugees. She asked Sheridan whether by any chance he knew a nice person who could give her some German lessons? She had a fondness for middle-European Jewish musical geniuses, and I think she was in love with the idea of Dolf even before she met him.

Neither she nor Dolf could get near to finishing the rock cake plonked in front of them by the waitress. Electrified by each other’s company, they were both overwhelmed by the feeling that (as Jan later put it) they were “one river.” They went across the road to the National Gallery and listened to a Bach piano recital by Myra Hess. Hess’s concerts in the empty-walled National Gallery (all the pictures had been taken down for safety), became a wartime emblem of the public’s thirst for beauty in a time of war.

When they came down the steps at the end of the concert, Jan remarked, “Bach is so all-right-making, isn’t he?” The compound adjective struck Dolf as perfect. Five weeks later, in the dark wintry days of the new year of 1940, they became secret lovers. They knew the relationship was doomed: Dolf would soon receive his visa for the United States, and be obliged to leave.

His visa arrived on April 28, 1940, and he sailed from Liverpool to New York on May 29. Jan, desolate, wrote him multiple letters, which he found pinned to the notice board in the hall of the refugee hostel on West 114th Street when he arrived.

But then a miracle happened – or was it just the amazing power of people in love, who need to be together, to engineer things so that they can be together?

Mrs. Miniver, published in the USA by Harcourt Brace, was the Book of the Month Club Choice. The publishers wanted Jan to travel to the USA to promote it. Then her husband Tony’s sister Rachel, who lived in New York, implored Tony to send his children over to New York for the duration of the war, with or without their mother. It was Tony who suggested to Jan that she should take the children. Finally the head of the American Division of the Ministry of Information summoned Jan to a meeting. He suggested that if she were to undertake a lecture tour in the United States, representing Mrs. Miniver, she could play an effective role as a propagandist for Britain.

With these three official magnetic forces pulling her across the Atlantic, and the other secret one, Jan could not resist. With her two youngest children Janet and Robert, she set sail for New York on 26th June, and the children were subsumed into Aunt Rachel’s welcoming family at 1 Beekman Place. Jan and her children would not see Jamie (the oldest son), or Tony, for five years.

Now Jan and Dolf could begin their new life as secret lovers living in the same city. The affair had to be kept hidden. Jan was touring the USA representing Mrs. Miniver, the very essence of the contented, devoted British housewife, and her husband, Tony Maxtone-Graham (John’s uncle), was in a prisoner of war camp in Italy. Discovery would have been disastrous for her cause.

Now, Bev:

There are two Bevs: John Beverley (“Uncle Bev”), and his niece Laura Beverley, our “Bev.” This is the story of how Jan Struther met “Uncle Bev” during the war years in New York, which led to Dolf meeting Bev.

Mrs. Miniver rose to number one on the U.S. bestseller list after it was published in 1940, and MGM snapped up the film rights. Two years later the Mrs. Miniver name became famous across the world, when the Mrs. Miniver movie came out, with Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon in the leading roles. “Propaganda Bureaus Are Struck Dumb With Envy”, ran a headline in the Toronto Globe. Almost by mistake, MGM had succeeded in making a movie of such intimate, shocking, tear-jerking power that even Joseph Goebbels was envious.

Jan became a celebrity in America, and she was in demand everywhere, traveling across snowy prairies during the gasoline-rationing war years, emerging onstage at the end of movie showings, blinking in the spotlight and speaking stirring words about why Nazism needed to be defeated and how every housewife could do her bit.

She was invited to grand dinners, and one of them was a fundraising Republican dinner party in New York in 1942, given by the Wells, Fargo & Company mail-carrying service.

I happen to be writing this on the day of the U.S. Presidential election in 2016, and am disconcerted by her presence at that Republican fundraiser. Jan was a Democrat who supported Adlai Stevenson so fervently in the 1952 election that she wrote a poem in anticipation of his victory and “threw herself onto the floor and wept” when he lost to Eisenhower. I’m not happy about her being at this Republican dinner party. But she was.

And if she hadn’t been, she might never have met the nice-looking older man next to her, John Beverley Robinson. As I write in The Real Mrs. Miniver,

“John Beverley was someone whom Jan instinctively warmed to and instinctively trusted. Such wisdom and understanding shone out of his eyes that she was disarmed. She felt an overwhelming urge to divulge to him the secret she had been keeping inside her breast since her arrival in America. She could not stop herself. “He’s called Dolf. I know you’d like him, and he you…I don’t know why I’m telling you…I’ve only just met you…””

Her instinct was right: “Bev” Robinson was a truly compassionate man, who kept Jan’s secret and did not condemn her for her double life.

From that evening on, Jan and John Beverley became great friends. A week later, she invited him to supper at her apartment in East 49th Street, and Dolf was there, and they sang folk songs to a recorder she had picked up at a junk shop in Mission, Nebraska. As I write in my book, “The room was alight with candles, music, poetry and laughter, and for a fleeting evening Jan and Dolf basked in the illusion that they were an accepted “couple”.

All this while, Tony and Jan were still officially married. They had married in 1923 and had been blissfully happy for the first ten years. But during the 1930s they had been increasingly unhappy, even if in public they continued to be a scintillating couple. One of the reasons Jan had written the Mrs. Miniver columns for The Times was perhaps to re-create the idyll of a perfect marriage, and to try to bring new life to her own ailing one. But it didn’t work. Tony’s suggestion that she should go with the children to New York gave them both an excuse to be apart for a while, without any official separation.

Jan wrote regular wifely letters to Tony, one of which (in 1942) contained the advice: “Pommel Rommel good and hard.” Tony was in North Africa on active service with the 2nd (Motor) Battalion of the Scots Guards, and on July 13 he was captured at the Battle of Gazala. He became a prisoner of war for three years, incarcerated in Chieti Camp in Italy – where, in a rather wonderful way, he blossomed as “Chairman of Chieti Entertainment,” producing 45 plays put on by the prisoners, including The Admirable Crichton, The Man Who Came to Dinner, and HMS Pinafore. As I write in my book, “While Jan was keeping up the morale of the lecture-going public in America, Tony was doing the same for the Chieti prisoners, many of whom might have sunk into despair but for his contagious good spirits.”

When the war ended, Jan did the dutiful thing: she said goodbye to Dolf and sailed back to London with the children, to be reunited with Tony. For a year she cut herself off from Dolf as she tried to rebuild her marriage. But the marital home in Chelsea, as they took the dust sheets off and tried to clean away the black Blitz dust, had become, as Jan put it, “an ice house.” In Jan’s papers, now kept in the National Library of Scotland, there’s a trove of letters Jan wrote to Dolf from 1939 till her death. The longest of them, 36 pages, is from October 1946, when he had cabled her to tell her he hadn’t fallen in love with anyone else and still loved her. Her letter vividly described the atmosphere of icy politeness in which she was barely surviving, and was a declaration of her utter love for Dolf. Tony also wanted an escape from the marriage, and now that the war was over, Jan no longer had to play the role of perfect Mrs. Miniverish ambassador for Britain. She was free to go, she and Tony were divorced, and she married Dolf in New York in March 1948.

John Beverley Robinson and his wife Marion had become close with the couple. In the summer of 1949, Jan and Dolf stayed with them on an island in Georgian Bay, Ontario. It was here, I believe, that they met John Beverley’s niece, Laura Beverley, also known as Bev – or, as Jan put it in a letter to Dolf, hardly disguising her stirrings of jealousy, “the she-Bev.” Jan saw instantly how attractive Bev might be to Dolf. He sent Jan a reassuring reply, and his faithfulness to her was indeed genuine and unswerving.

But after Jan died of cancer at the tragically young age of 52, Dolf married Bev. As he said to me in 1999, “we’ve had forty-three years of cloudless happiness together.” As I write in the epilogue to my book, “they were united in their love of architecture, German, French and English literature, music, and conversation with friends young and old, in their book-filled apartment with a Mozart or a Beethoven sonata open on the grand piano.”

(If you’d like to read The Real Mrs. Miniver, it can be ordered directly from Slightly Foxed publishers, https://foxedquarterly.com/shop/the-real-Mrs.-miniver/ )

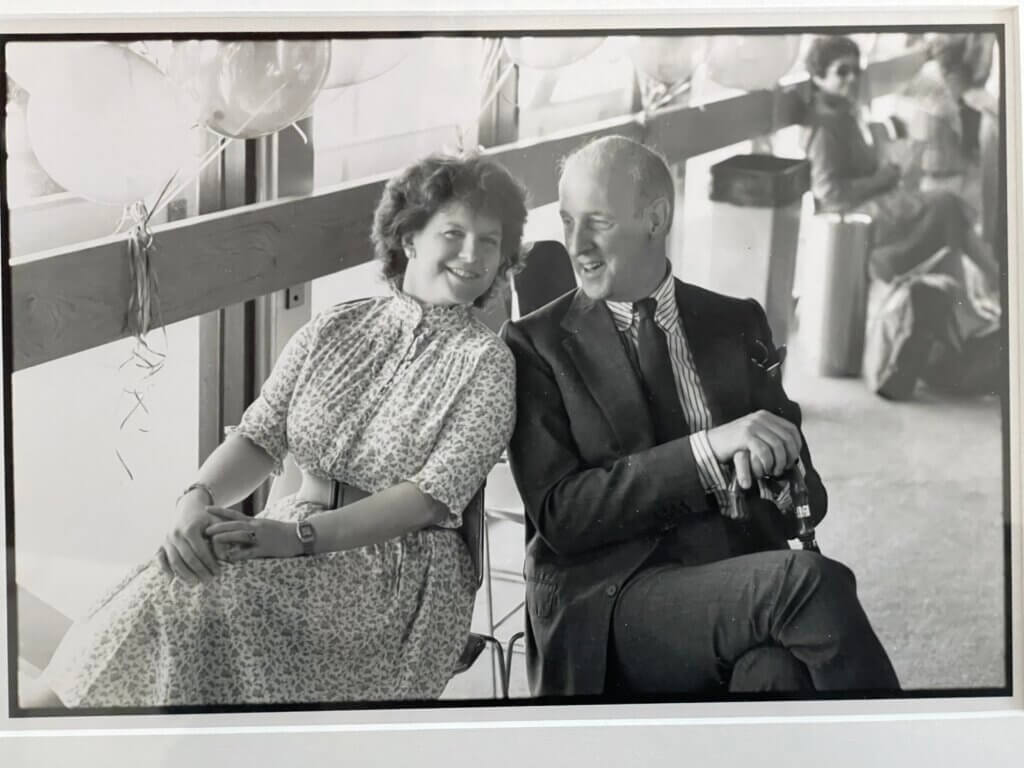

Editor’s note: Mary Bergeron was an 11-year-old camper at Apple Hill Summer Camp in New Hampshire when she met, and formed a lifelong friendship with, the camp’s founder and director, Bev Placzek. When Mary moved to New York many years later, Bev and Dolf introduced her to John. John and Mary were married on board the SS Rotterdam in New York Harbor in 1981. They honeymooned on the ship, which set sail later that day, with John, as usual, working as a paid lecturer aboard.

Below is a photo of John and Mary, probably taken in the late 80s, shortly after boarding another ship for a cruise or crossing. They were an exceptionally happily married couple, who rarely, if ever, had an argument.