Marine Corps

By JOHN MAXTONE-GRAHAM

From the memoir…

I was drafted into the United States Marine Corps one rainy October morning of 1951. Curiously, I began the day believing I was being drafted into the Army.

That morning, a group of 21 potential draftees congregated at Hyannis’s railway station shortly after dawn to board an early train to Boston’s South Station. From there, we were bussed to the United States Army’s Induction Center.

After we underwent a preliminary physical examination, we were advised of a startling development: 6 of the 21 members of our detachment were to be drafted into the Marine Corps rather than the Army. The Korean War had just started and the Marine Corps was in need of replacement personnel; their standard volunteer numbers were inadequate.

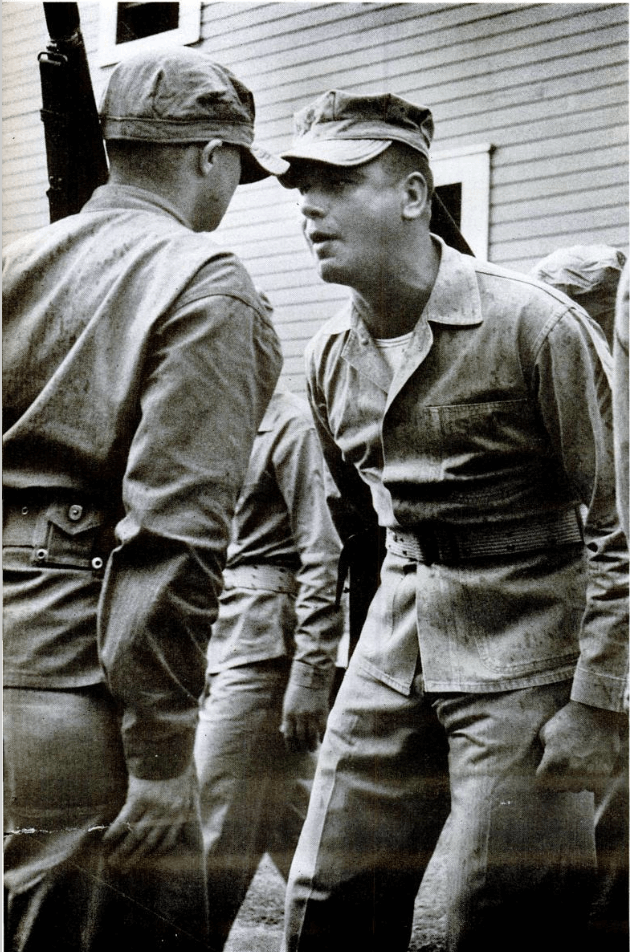

By coincidence, only a few months earlier, an issue of Life Magazine had published a pertinent and rather scary photo essay, including a black-and-white close-up of a formidable drill instructor at Parris Island named Sergeant Trope.

The article inside documented the demanding and arduous treatment that Parris Island recruits could expect.

We had all read that issue of Life and its unflinching portrayal of boot camp rigors; as a result, nothing about Parris Island seemed enticing. Sergeant Trope, it seemed, would not convince any of that 21-man Hyannis detachment to join the Marines; in fact, the very opposite would doubtless prevail.

But a remarkable and very curious thing happened. A change of heart occurred to six of us during our physicals. We decided, independently, that the Marine Corps option would be the preferable choice.

I am not certain what persuaded me. It may have been something as corny as a recruiting poster, showing a lantern-jawed Marine clad in impeccable dress blues. Or it may have been ruminations about the distinction offered by the Corps as opposed to the much larger Army’s humdrum anonymity. Whatever the reasons, we six all agreed and conveyed our preference to the officer in charge, who was delighted to hear the news.

Perhaps I should preface that incident with a preliminary wartime quest of mine. I had discovered that Brown was, for some reason, a potent supplier of candidates to the Central Intelligence Agency. More than one faculty member, including one I much admired, had worked for the CIA; several graduating seniors also applied to the agency. I liked the idea of working for the CIA as an alternative to being drafted, so I applied, filling out long, complex government forms that revealed my British background as well.

The upshot was that I was rejected; apparently my divided loyalties between the UK and the US did not appeal. I was told by a supportive telephone voice from Washington that in the event they changed their minds, CIA recruiters might well notify me literally the day before I was to be devoured by the Selective Service maw. But no such call materialized; hence, that early morning train to Boston.

We discovered that, thanks to our popular joint decision, we six potential marines would be given an extra night’s stay in Boston, an exhilarating reward. I knew a young Bass River woman who was a sophomore at Radcliffe. I managed to find her dormitory number, called her and invited her out to dinner. Then, since it was still early, we sat on a park bench and, in the parlance of the day, necked.

It was a lovely evening, but it proved a relationship with no future. Not many weeks after I arrived at Parris Island, I heard that she had consented to marry another man, a Bass River summer resident and also, curiously, a distant cousin of mine.

Our six-man marine detachment met at South Station early next morning and boarded a troop train. For some reason, I was put in charge of our carriage. We were surrounded by dozens of noisy and aggressive Marine recruits; their reckless bravado concealed homesickness and, I am convinced, worry about their ordeal to come.

Our train proceeded farther south in the United States than I had ever been. We passed through Baltimore, Washington and Richmond, and finally halted at the small station for the town of Beaufort, South Carolina. We were ordered off the train and then, holding our suitcases, waited on a nearby platform identified only by the name Yemassee.

This was the western end of a desolate rail spur that would carry us eastbound to Parris Island, the recruit training depot for all those joining the Marine Corps east of the Mississippi; those corralled from west of the Mississippi would head in the opposite direction, to San Diego.

A rickety train arrived and uniformed NCO’s herded us up into antiquated passenger cars. Conversation and smoking were forbidden. The train rattled and groaned for half an hour before lurching to a stop. We had reached Parris Island.

We recruits fell out in a ragged line and were marched, sort of, to a mess hall for a meal. The food was all right, but the difficulty was coping with what to drink with it. There were no glasses, merely stainless steel containers like soup bowls. We filled them with either grape juice or coffee and drank our fill.

After lunch, we were marshaled out on the sidewalk into a rough version of several combined platoons, and shuffled off towards a maze of Quonset hut barracks. We joined several dozen other men as fellow members of our recruit platoon. Most of these new companions were West Virginians, including one Black man nicknamed BeeBop. He was short and very funny, and we became instant buddies.

None of our original Boston contingent ended up in my platoon; they had been siphoned off to other platoons and scattered around the base, but I would re-meet some of them back on Cape Cod after boot camp.

Surprisingly, we were then left on our own for the rest of the day. There was no drill, no muster, no organizational compulsion. That would all happen on the morrow, a forbidding and exhausting day called, for some reason, “Hygienic.”

We were assembled and marched off to enter the first of a series of warehouses. First stop was for a photograph, not for identity but publicity. A white dress cap, complete with Marine Corps insignia, was perched on our heads and we were wrapped — like corpses — in a “dress blues” tunic, arms thrust into sleeves before the garment was laced hastily up the back. To all intents and purposes, we appeared to be fully dress-blued Marines.

Those photographs were immediately dispatched to everyone’s hometown newspapers, in which they were inevitably published. Mine appeared in both the Cape Cod Standard Times and the local Yarmouth Register. It was all part of the Marine Corps’ relentless publicity mania; neither Army nor Navy recruits were subjected to the same ritual.

Next came dog tags, two of them, stainless steel with rounded ends suspended on steel chains around the neck. My name appeared in raised letters on each tag, together with “O,” indicating blood type and “P” for Protestant. At one end of both dog tags there was a notch, which, I was later told, was used in the event the wearer was killed in combat. The notch would be positioned between one’s two front upper teeth and chin, then bashed upwards with a rifle butt, locking it firmly in place. (Editor’s note: This widespread urban legend appears not to be true. Apparently the notch was to hold the dog tag in place in an “Addressograph” machine.)

Then impatient and demanding Marine personnel doled out clothing and equipment. I recall standing, at one point, in an open doorway, clad in skivvies and an open shirt, with two loose khaki ties joining the dog tags draped around my neck.

One surprising thing I noticed was that none of my fellow recruits had the faintest idea what size clothing they wore. When those West Virginians were asked for it, they pleaded ignorance; their mothers always bought their clothing and they hadn’t a clue about size. This didn’t speed up or ease the distribution process, and I discovered one curious advantage I had over my fellow recruits: years of boarding school. Having been dispatched to Windlesham [Windlesham House School, in Sussex] at age nine, I had learned early on to cope with alien and sometimes hostile environments.

Slowly, we accumulated an awkward mountain of new possessions: duffel bags, combat boots, socks, dungaree jackets and trousers, belts, caps, even a bucket. Some of this clothing we put on at once, replacing our civilian clothes. As we circulated around the supply tables, we carried more and more away with us, and somehow carried our suitcases as well.

Later that afternoon, we were assembled outside one of the base’s postal facilities. There, we filled out labels on which we printed our home addresses before pasting them onto our suitcases. These were then dispatched home at government expense, and we returned, dressed in dungarees and caps, to our platoon’s Quonset hut. Immediately, we were told to commit our new belongings to steel lockers spread along the rounded walls nearest our double-decker bunks.

That half-round Quonset hut became our home for three months, apart from a fortnight spent at the rifle range. We met our two drill instructors, Sergeant Doudna and Corporal Baker, who would shout us into shape. We were taught elements of basic drill, learning how to stand as a platoon and march in the same formation. We were also issued M1’s and were told immediately that they were not guns, but rifles. A simple rhyme made things clear:

“This is my rifle, this is my gun;

This is for killing, this is for fun.”

There was a harsh but efficient punishment meted out to recruits who continued to use the wrong term. They had to sleep with their squad’s rifles in the bunk with them, operating rod handles facing uncomfortably upwards. Just one night of that particular torture taught them the difference.

At night, recruits took turns on fire watch, which involved circling the platoon’s three Quonset huts for four-hour stretches. Unless it was raining, I found it not a bad chore, providing a rare and oddly welcome isolation from the remainder of the platoon.

We wrote home, describing what boot camp was like. I recall asking my mother to send me as soon as possible some effective insect repellent. Stealth seemed advisable — one of the DI’s favorite amusements was to muster the platoon half an hour before evening mess call. It was near sunset, a time when local mosquitos and gnats started coming out in force. If you moved or attempted to slap them, you were called out of ranks and punished with a dozen pushups or sit-ups.

The repellent arrived concealed cleverly inside a loaf of bread, and I was able to sneak some onto my face and neck each afternoon. When the platoon was fallen out for one of those infuriating bug-fests, the creatures stayed away, hovering around my face but never landing. Sergeant Doudna never cottoned on to my ruse and it was the only time I was ever able to flummox the DI’s.

There came a time when our entire platoon was assigned a week’s mess duty; but Messrs. Doudna & Baker kept me on, as they were allowed to, as a kind of permanent platoon fixture, either in the empty hut or frequently in their quarters, polishing boots, sweeping the floor or tidying up. Both men seemed intrigued by me, possibly because of the tone and demeanor I adopted, as though I was a very correct English butler, always responding, as perhaps no other recruit ever had, with a brisk “Very good, sir!”

They were also addicted to country music, broadcast from a Cincinnati radio station called WCKY. Even in faraway South Carolina, its signal came in loud and clear, repetitious and hence unforgettable. The station’s favorites were Hank Williams and Lefty Frizell; their songs seemed to be played nonstop.

I bought their records after I got home, and I play them to this day as potent reminders of boot camp: “The Mom and Dad Waltz,” “If You’ve Got the Money, Honey, I’ve got the Time,” “I Want to be With You Always,” “Always Late” — I know them well now, though I had never heard them before Parris Island.

We were drilled each day on a demanding obstacle course, vaulting over walls, swinging on suspended ropes across muddy bogs, crawling on our bellies through ditches with live machine gun rounds being fired overhead, crossing water obstacles atop peeled and slippery tree trunks, and, most demanding, having to climb a rope suspended from twenty feet above. I finally managed that climb after enormous effort, developing sufficient upper-arm strength to get myself, utterly exhausted, to the top.

Rifle range firing was equally demanding. Our M1 slings were deployed for the first time. We were taught to rig them so that our left arms were enclosed tightly inside them. Then we sat on the ground, with knees spread and slings locked above our elbows, firing at cloth targets ranged along the “butts,” as the target area was called.

If one fired and missed completely, what was known derisively as “Maggie’s drawers” appeared: a mocking red flag waved back and forth by butt personnel to indicate no target contact.

Every recruit’s rifle range achievement would be acknowledged publicly. We left the range with a record that could be emblazoned on our dress uniforms, the first decoration Marine Corps recruits ever receive. First Class Rifleman was mine, I still recall.

We spent final weeks preparing for a battalion-sized “march-past.” The platoon had absorbed and perfected the drill drummed into us daily. Recruit platoons were divided into a trio of squads, each squad composed of three four-man fire teams, with a squad leader marching at the head of the twelve-man column, carrying a pennant on a staff. The parade was accompanied by Parris Island’s regimental band, and the combination of marching men and stirring Sousa music was irresistible. There we were, among thousands of fellow jarheads, marching in impressive order, pennants flying, wearing dungarees, scuffed combat boots and cloth caps, but feeling and looking like a million dollars.

One final occasion signaling the end of basic training was yet another photograph, this one a platoon group taken on ascending bleacher steps. We wore for the first time our dress uniform, not dress blues but dark green jackets, trousers, peaked caps and polished boots. We had spent hours, literally, spit-shining those shoes to mirror-like perfection. We wore no Sam Brown belts because the Marine Corps had stopped issuing them after discovering that Marines used them lethally in late-night brawls with rival servicemen.

At six feet four and a half inches, I was the tallest recruit and so positioned in the center of the rear-most rank atop the bleachers. Sergeant Doudna and Corporal Baker, in their dress uniforms, stood to attention in front of us, and each recruit received a large blowup of that platoon portrait. Then we were sent home, in uniform, arriving just in time for Christmas.

After some brief, welcome leave, I went south again, by train, to North Carolina’s Camp Lejeune, a sprawling base for both a division of Marines and an air wing. Because I had worked on the newspaper at Brown, the Brown Daily Herald, I was sent to the base’s PIO or Public Information Office. I did interviews and wrote stories about men, tanks, and occasionally aircraft.

I also learned how to operate as independently as possible. The ritual I adhered to was perfect: always carry a clipboard and pencil, and stop periodically to scribble apparent notes. It always worked: never was I interrupted or dragooned for other chores.

Since I was a college graduate, I was asked by the colonel who headed the PIO whether I might be interested in applying for The Basic School at Quantico, to become a commissioned officer. We talked at length, and one thing that I recall from that interview was his flattering evaluation of my voice.

“You speak remarkably well,” he confided. “I have never before heard an enlisted man who was so vocally polished.” It was the first praise I ever received in the Marine Corps, and reminded me of my Parris Island drill instructors’ fascination with my accent. The colonel said he would add my name to his Quantico listing.

Before my orders for Quantico arrived, I had a horrifying experience that occurred during a trip to Washington, D.C. for a weekend’s liberty. A private first class’s wages were minuscule, and the only way one could get as far as Washington and back was by joining a car being driven there and back for a nominal ten dollars per passenger. I signed up for a car that, together with its owner/driver, would carry five other passengers. One Friday night after our week’s duties had been completed, we found the driver, handed over our round-trip sawbucks and were driven, at breakneck speed, to Washington. We were to rendezvous with the driver on Sunday at midnight for our return to Lejeune.

I recall very little about that weekend. I booked a room at the Dupont Plaza Hotel and, on Sunday evening, called on my old friend from Brown, fellow marine and now Lieutenant Anthony Marshall, he of the late lamented Course Critique. He was now posted in the nation’s capital, and I stopped by to say hello to him and his wife.

(Editor’s note: John and Anthony Marshall collaborated on the Course Critique, Brown’s student guide to courses. There is a link to Anthony Marshall’s New York Times obituary in the section on John’s time at Brown.)

I talked about my hair-raising ride up from Lejeune and confessed that I was worried about the return, which would start in a couple of hours, at midnight. Tony was sympathetic, and pressed a couple of glasses of brandy on me as a welcome and effective relaxant.

After he drove me to the car rendezvous, I bade him farewell. Then I gathered with the same five passengers and the same awful driver. Promptly at midnight, we set off.

I was in the back seat on the right-hand side, and had draped my raincoat over my face for protection from the lights of approaching cars. Thanks to the brandy I slept for an hour or so, but I was woken abruptly by a disruption of squealing brakes and tires, which climaxed moments later with the jarring impact of a crash.

Most likely, our driver had fallen asleep at the wheel and careened straight into oncoming traffic. The car was demolished by an oncoming truck, as though sliced by a huge knife from the hood ornament back to the left rear wheel. Though all his passengers survived, the driver was instantly killed. My head thumped hard against the back of the front seat. In a daze, I climbed out of the half-wrecked vehicle, walked around to the trunk and extricated my suitcase. I was ready to hitch another ride aboard one of dozens of passing cars.

But I was prevented from doing so by the police, and my fellow passengers and I passed the remainder of the night camped out in the local police station.

The next morning, all five of us were interviewed by the trucking company’s legal representative, who wanted to make sure that we were not going to press charges. Only after agreeing that we would not were we released to resume our journey, this time as bus passengers. The police had telephoned Lejeune, and we were checked in on arrival later that afternoon.

The only aftermath was that when my orders for Quantico arrived the following week, I had to have my Basic School ID photograph taken. The thump of my head on the back of the car’s front seat had produced two black eyes that made for a rather grim-looking officer candidate.

The first thing I was instructed to do on arrival at Quantico was to ink over the PFC (Private First Class) stripes adorning my dungaree jackets. There must have been over a hundred of us from Marine Corps bases all over the country, some of them tech or master sergeants. But once our stripes were inked out, we were all rendered identical: “mustangs” was our group descriptive–enlisted men hoping for a commission up through the ranks.

The initial phase, known as the “Screening Course,” was designed to weed out applicants deemed unfit for further officer training. This lasted for two months, and we were housed in a single Quantico barrack. In addition to drill, we were embarked on a series of tests. A great deal of speech-making was involved — we were ordered repeatedly to explain or analyze a topic. We were either assigned a topic or produced one of our own. I remember giving one scrupulously instructional talk about how to make the perfect dry martini. Officers, we realized, were forever making speeches to their men, and we had to hone our skills for that inescapable eventuality.

Lieutenants and captains on the staff hounded us daily. They were martinets about weapon inspection. During one rifle inspection, it was discovered that I had inadvertently left the entire trigger mechanism loose. Patiently and with soul-destroying finesse, the instructor disassembled the weapon in my hands.

I redeemed myself somewhat by teaching members of my platoon the British Manual of Arms, which I clearly recalled from my days at Sedbergh School and its Junior Training Corps. It is very different from America’s. I taught my chaps to do a British “present arms,” for instance, with their right foot locked slightly behind the left; also, to achieve “port arms” à l’anglais and to march with M1 rifles in the British manner, flat on the shoulder rather than perched upright. It took much discreet practice, but when unveiled, the British Manual of Arms was a huge success, attracting a great deal of attention.

When the final day of our Screening Course arrived, fully a third of the class members were disqualified. Those men disappeared magically very early one morning with no farewells, dispatched back to the enlisted outfits from which they had been recruited. Those of us who had made the cut were issued with the precious gold bars of second lieutenants. Like all newly minted officers, we eagerly sought and received the obligatory first salutes from any enlisted men we encountered.

The next phase would consume seven humid months. All the newly commissioned officers were divided up into platoons. We discovered immediately that the enlisted NCO’s instructing us could pack a great deal of venom and scorn into their words, even though we theoretically outranked them, and their every remark had to conclude with an obligatory “Sir.” There were senior officers instructing us as well, and they too made it their business to handle the newly commissioned contingent vigorously and ruthlessly.

We attended interminable lectures in long Quonset hut classrooms, each of us seated on a hard wooden chair with a small table in front of it. Any officer caught sleeping during a lecture was made to stand at attention behind his chair until dismissed, but we quickly learned a trick: by opening the table’s single drawer and wedging both elbows into it, we could nap stealthily while creating the impression that we were rigidly attentive.

There were occasional outings into the surrounding Virginia hills. A local ice cream truck that someone had tipped off about our schedule would come grinding up the slopes at noon. Craving relief from the oppressive heat and humidity, we were eager customers.

There were repeated ordeals on the parade ground as well. “Full kit inspection” involved laying out the contents of one’s pack atop a poncho on the parade ground. Every required item of clothing — shirts, trousers, jackets, socks and boots — had a specific place in the display. But it was a common Basic School practice to fill our packs with lightweight bogus bulk to lighten the load while keeping the pack’s dimensions as they should be.

This necessitated a frantic replacement shuffle: as the inspection party moved on, bogus lightweight fillings had to be discreetly and quickly replaced with heavier originals before the officer and NCO inspectors arrived; once they had passed, these missing bits and pieces were hastily and perfectly transferred down the line to the next inspectee.

The Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr., was often on the base, and it was a matter of some interest to me that his “Quarters #1,” as they were identified at Quantico, contained not only himself and his wife but also their attractive single daughter, Anne. I had somehow managed to meet her at an evening gathering, and we had become friends. It was with only the slightest trepidation that I advised the commanding Basic School officer that I was invited to Quarters #1 for dinner on several occasions. Happily, because the invitation came from the Shepherds, permission was always granted.

One of my great friends was a highly amusing and entertaining man from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, named Bob Cudlip. Bob had a Cadillac convertible, and he drove me to Grosse Pointe for a Fourth of July weekend. I spent a celebratory holiday weekend with the Cudlip family. During a dance at the Grosse Pointe Country Club on Saturday evening, I met and fell immediately for a young woman who lived nearby named Katrina Kanzler. I asked her to come out onto a pier stretching out into Lake Michigan, and she refused the invitation in no uncertain terms.

Months later, on our way to the fighting in Korea, we stopped in Kyoto, Japan, where I bought a box of a dozen Christmas cards. All twelve were destined for family members, but as luck would have it the box contained a thirteenth card. I decided to send it to Katrina; our friendship continued and grew, and several years later we were married.

Editor’s Note: This is where John’s memoir of his Marine Corps service ends. Unfortunately it does not continue through his time in Korea, which included six months of combat. Some of the photos in this section were taken in Korea, however. He was a Lieutenant in Korea, and promoted to Captain upon discharge.

John’s cousin David Townsend also served in the Marine Corps in Korea. In 2020, at age 90, after recovering from Covid-19, David gave an account of his time in the Marines and of the day he spent with John in Korea. (John and David were very close growing up, and stayed great friends throughout their lives. David was one of the family members who traveled to New York to see John in hospice in the week before he died.)